1959-1965: Early Economic Strategies

Surviving Our Independence

In 1959, Singapore achieved self-governance after years of struggle. The People’s Action Party (PAP) was voted into power in the Legislative Assembly general election, becoming the first full elected government of the self-governing state of Singapore on 5 June 1959. Mr Lee Kuan Yew was appointed the first Prime Minister.

1959-1965: Early Economic Strategies

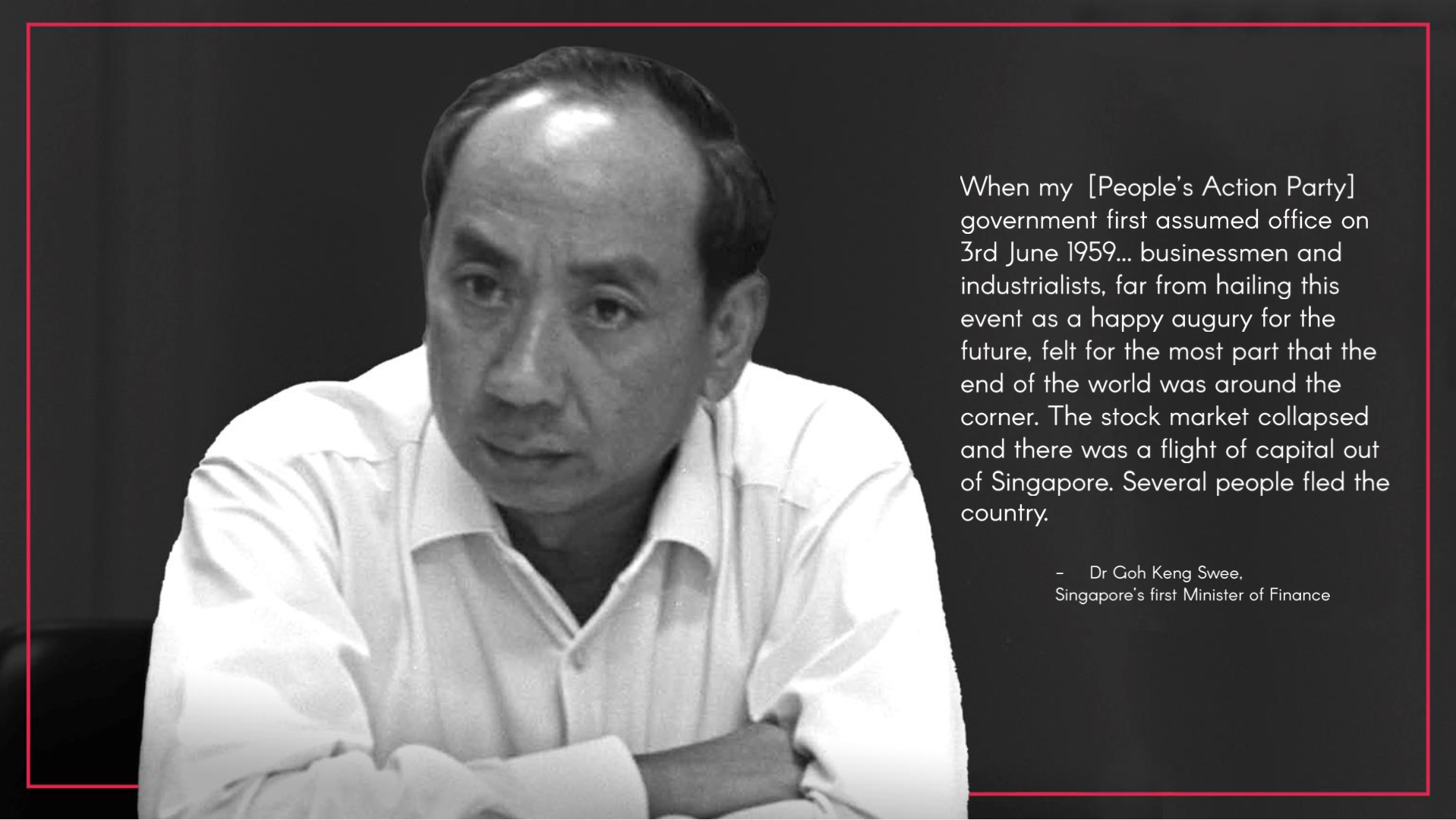

(Image: A scene of a typical squalid side street in the Central Area; HDB Annual Report 1965; BookSG)

(Image: A scene of a typical squalid side street in the Central Area; HDB Annual Report 1965; BookSG)

The new government faced huge problems almost immediately. While Singapore had recovered from the devastation of World War II, the country was derelict: the city centre was overcrowded, buildings were deteriorating, and nearly 70% of the population lived in slums. Moreover, the economy was largely trade-based. As there was hardly any local industry to create meaningful jobs for a growing population, unemployment rate was in the double digits.

The economy thus became a key priority. The founding leaders of Singapore had in place two key economic strategies: rapid industrialisation and merger with the Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, and Sarawak.

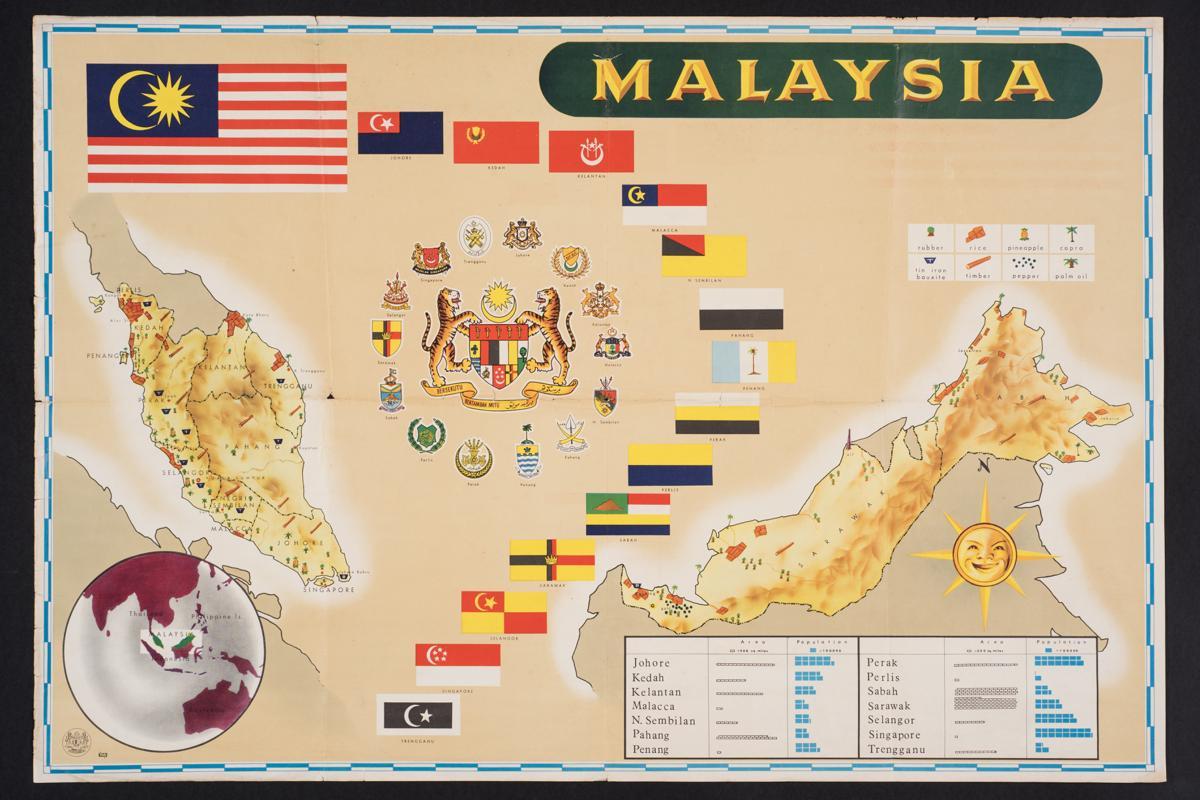

(Image: Map of Malaysia, 1963-1965; National Museum of Singapore via Roots.sg)

(Image: Map of Malaysia, 1963-1965; National Museum of Singapore via Roots.sg)

1961: A Plan for Rapid Industralisation

In 1961, a team of United Nations (UN) economists led by Dutch industrialist Albert Winsemius visited Singapore to advise the new government how to develop its economy. They issued a report, “A Proposed Industrialisation Programme for the State of Singapore”, which outlined a plan to embark Singapore on a path of rapid industralisation to absorb the large numbers of unemployed workers.

They recommended that in order to end unemployment, over 200,000 jobs had to be created within 10 years. Until that time, the local economy was dominated by trading firms and entrepôt trade. While trade formed the basis of Singapore’s prosperity during the colonial period, it left our economy particularly vulnerable to the global prices of tin and rubber. Furthermore, entrepôt trade could not generate enough jobs to absorb the rising numbers of unemployed workers.

The lead agency tasked to undertake the critical role of implementing the industrialisation plan was the Economic Development Board (EDB), which was set up in 1961. Taking over from the Singapore Industrial Promotion Board, which was founded in 1957, EDB had a much larger remit and capital base. It was armed with $100 million over the period of 1961 to 1964 to drive industrialisation in Singapore. Its first task was to build the necessary infrastructure to support the plan.

One of its first tasks was to develop Jurong into an industrial estate, as part of a push to create labour-intensive industries that would generate jobs for the people. Some of the early factories produced items such as garments, toys and wigs. This was only the beginning of the story of Jurong.

1963: Formation of Malaysia

The economic rationale for a merger with Malaya, North Borneo and Sarawak to form Malaysia was clear. A combined market of about 12 million people would overcome the limitations of Singapore’s small market size by enabling the growth of local firms, and generating jobs and income for Singaporeans.

However, this was complicated on several fronts.

The years after WWII were highly unstable, and Singapore and the rest of British Malaya saw violent anti-colonial and communist insurgency. There were labour strikes, for instance, particularly from 1963 to 1968.

This was severely disruptive to the economy, making Singapore unattractive to foreign investors. “The running joke was that a factory would be set up on Monday and all sorts of banners screaming ‘Exploitation of Workers’ would be hung up by Friday,” shared I.F. Tang, who was part of the UN team of experts.

Furthermore, in 1963, the newly formed Federation of Malaysia came under attack by Indonesia. Back then, Indonesia believed that Malaysia was formed to contain Indonesian influence in the region. Thus, it embarked on Konfrontasi, a low-intensity confrontation between Indonesia and Malaysia.

Led by then-President Sukarno, Indonesia carried out acts of subversion and sabotage, such bombings, to destabilise Malaysia between 1963 and 1966.

Moreover, it cut trade ties with Malaysia, hoping to disrupt its trade and cripple its economy. As a result, Singapore’s trade with Indonesia shrank. Between 1963 and 1964, imports declined by 23% while exports declined 31%.

Indonesia also carried out a series of bombing attempts in Singapore, which were aimed at causing damage to Singapore and rattling foreign investors. On 16 November 1964, an attempt by 10 Indonesian commandos to sabotage an oil installation was foiled. In 1965, the tragic bombing of Macdonald House along Orchard Road claimed three lives and injured 33.

In addition, Singapore’s union with Malaysia was also troubled from the start.

Then-Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman and then-Prime Minister Lee fundamentally disagreed on what kind of society they wanted. While PM Lee insisted on a society where all races were treated equally, Tunku believed in the primacy of the Malays in Malaysia. At this time, racial violence was also rife across Malaysia.

Moreover, the anticipated economic benefits from the merger were less than expected. The increase of the manufacturing share of real GDP was modest – from 16.9% in 1960 to 19.% in 1965. Real GDP grew at an annual compound rate of 5.7% during this period. Some 21,000 jobs were created in manufacturing, but the unemployment percentage still hovered in the double digits. This persuaded then-Finance Minister Goh Keng Swee that the benefits of the common market were not as substantial as he once believed.

The political, social and economic difficulties of the merger led to a momentous decision. Expelled from Malaysia on 9th August 1965, Singapore was on our own. We no longer had a common market of 12 million consumers to support our growth. With no natural resources, a tiny population and rising unemployment, Singapore’s leaders were faced with a dire situation.