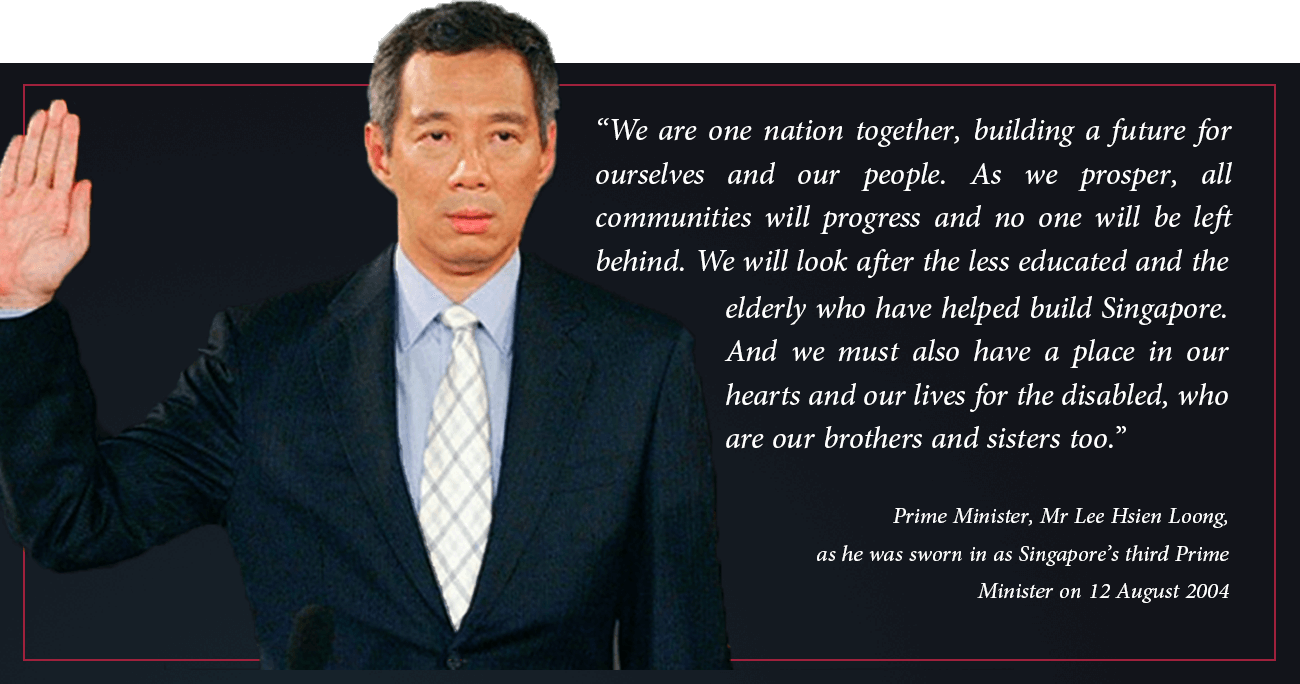

Building and Maintaining a Caring Society

Building and Maintaining a Caring Society

As Singapore progresses, new fault lines on issues such as class, immigration and identity have emerged.

In a 2017 study on social capital in Singapore where 3,000 Singapore citizens and permanent residents were interviewed, the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) concluded that the sharpest social divisions may now be based on class, instead of race or religion. The study found that Singaporeans who live in public housing have fewer than one friend who lives in private housing, and that people who study in elite schools also tend to be less close to those in non-elite schools, and vice-versa. It was also observed that while the respondents could easily name a friend of a different gender or age, and even race and religion, they were unable to name someone from another class.

Likewise, a report by the World Economic Forum released in January 2020 ranked Singapore 20th out of 82 countries surveyed on social mobility. Singapore performed poorly on fair wage distribution and social protection, ranking 51st and 61st respectively.

This is a problem for Singapore. Professor Tommy Koh, a veteran diplomat and special adviser to the IPS, said at a dialogue in 2018, that despite Singapore ranking among the top in terms of per-capita income, there are still many Singaporeans who live in poverty. His research estimates that 100,000 to 140,000 households lack the means to pay for their basic human needs. Poverty is very much a real issue in Singapore. Singapore’s leaders have acknowledged this potential time bomb of social inequality among Singaporeans, and that something needs to be done.

PM Lee also spoke about inequality in a dialogue in 2018, noting that displeasure came from being stuck in a poverty cycle, and a lack of opportunities to work hard and improve their lives. In contrast, though previous generations had to work hard for their livelihoods, there was greater socio-economic mobility.

To enhance social mobility within Singapore, many government policies are targeted at creating a more inclusive society with opportunities for all.

For example, steps have been taken to address the disproportionate number of students from well-off families in brand-name schools. Since 2014, all primary schools are required to keep at least 40 places for children with no connections to the school. From 2019, one-fifth of places in affiliated secondary schools are set aside for students who do not benefit from affiliation.

Advancement in schools is also based on merit, using results from national examinations. Tuition grants and financial aid are available to ensure education remains accessible to those in financial need. These policies help create a school environment where students from varied backgrounds can interact.

Many attempts have also been made to tear down the metaphorical fences between those living in public and private homes. For example, in June 1998, the People’s Association (PA) formed Neighbourhood Committees within private estates to promote active citizenry and neighbourliness, as what the Residents’ Committees in HDB zones do. Joint activities for both groups have been regularly organised since then.

.jpg) (Image: National Archives of Singapore)

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

Sports have also been a way to bring people together. Joining sports clubs at community centres is free, allowing avid players of the sport to mingle and get to know each other.

To ensure that no one is left behind, schemes such as SkillsFuture and the Progressive Wage Model (PWM) provide opportunities for low-wage workers to upgrade their skills and take on more highly skilled work. For instance, SkillsFuture aims to help Singaporeans develop and master relevant skills that will help them in their careers. To ensure that all have the opportunity to access courses for self-improvement, credits are provided for Singaporeans aged 25 and above to use for courses. There are also subsidies are also provided for certain courses and after meeting certain requirements, such as up to 90% subsidy on selected courses for Singaporeans aged 40 and above. This initiative helps to make training courses accessible to all, and help boost employability to achieve higher paying jobs, regardless of one’s starting point.

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

Working towards a multi-abled society

Those with disabilities are also given opportunities to improve their lives and contribute to society. A national road map – the Enabling Masterplan – was launched to improve the lives of the disabled and support their caregivers. The first masterplan was unveiled in 2007; the second in 2012. The third, launched in 2019, saw the creation of two new workgroups to help people with special needs live independently and improve their chances of getting a job. One group will look at making it easier to access lifelong learning opportunities and employment pathways, while the second will assess how technology and design in homes and the community help those with special needs live independently.

(Images: National Archives of Singapore)

(Images: National Archives of Singapore)

Total funding for special education schools have also risen by about 40 per cent over the last five years, ensuring that children and teenagers with intellectual difficulties are able to get an education. The number of special needs schools now stands at 19, with three more in the works. More mainstream schools are also opening their doors to students with mild special needs, with the help of allied educators. Currently, 20 per cent of students with special needs are in special education schools, with the rest, or 26,000 students, in mainstream schools. This figure has doubled from 13,000 in 2013.

While the government’s social provisions have broadened, they remain anchored in the basic principles of self-reliance, individual effort and personal responsibility. As former DPM Tharman famously told a BBC presenter on 7 May 2015, when pressed about the concept of a safety net, “I believe in the notion of a trampoline.” Social assistance in Singapore is not supposed to provide a comfortable life but to spur citizens on to get back on their feet.

Relying on government support alone is also insufficient, and it is up to the individual to take initiative and put in the hard work. In his 2012 National Day Rally speech, PM Lee noted that there a need to “maintain a sense of mutual responsibility amongst ourselves and especially on the part of those who are more successful than others”.

How have we fared in creating a multi-abled society and what more else has been done?

In August 2021, Singaporeans celebrated the achievement of backstroke swimmer Yip Pin Xu in winning two gold medals at the 2020 Tokyo Paralympics, becoming the country’s most decorated Paralympian.

Many were also puzzled why the financial reward that the five-time Paralympic Gold medallist, who has muscular dystrophy, received for each gold medal was just $200,000, compared to the $1 million awarded to an Olympic gold medallist.

There were social media posts, letters to the Straits Times forum and several members of Parliament asking if more could be done to reduce this disparity in cash rewards for able-bodied and para-athletes. Eventually, DBS stepped forward to as a sponsor for the Singapore National Paralympic Council. It said that it will match the council’s Athletes Achievement Awards (AAA), the cash incentive scheme for Singaporean athletes who win medals at major para games. This meant that Ms Yip received $800,000 for her achievements, double what she would have originally received for her two golds at the Paralympics.

The public discourse about this topic of a disparity in reward reflects the growing attention paid by Singaporeans to fostering an inclusive, multi-abled society in all areas – be it for sports, arts, education or the workplace.

It also points to the direction that Singapore is working towards an inclusive, multi-abled society.

Singaporeans like Ms Yip have won the highest admiration from her fellow citizens because of her contributions to sports and community work, including serving as a Nominated Member of Parliament. In recognition of her strong contributions to Singapore and society, Ms Yip became the first recipient of the President’s Award for Inspiring Achievement in February 2022.

As a trail-blazer, she has also spoken about more parity and accessibility to resources for people with disabilities and disadvantaged backgrounds – an issue that other Singaporeans such as Ambassador-at-large and Tembusu college rector Tommy Koh have raised as well.

“I can empathise with why many of our disabled citizens feel like second-class citizens,” Professor Tommy Koh wrote in an essay on 27 May 2021 . “My ambition is to help level the playing field for them. My dream is that one day, all our disabled citizens will feel like first-class citizens.”

People with physical disabilities still face challenges in finding employment in Singapore, despite the many incentives offered by the Government, Professor Koh pointed out. He recalled that artist Chng Seok Tin, who was awarded the Cultural Medallion in 2005, had applied for a teaching position with a Singapore tertiary institution. However, she was not granted an interview when the employer found out that she was blind.

But there is change on this front, with growing awareness of the need to provide equal opportunities for all Singaporeans. A growing number of local companies have launched initiatives to provide more jobs for people with disabilities. For example, United Overseas Bank hires people with autism and hearing impairments for roles such as document archival; Uniqlo Singapore created a mentor-buddy system that pairs store managers with its workers with intellectual disabilities; the National Library Board has trained dozens of people on the autism spectrum to do scanning and digitalising tasks. Meanwhile, ride-hailing and food-delivery service provider Grab hires staff with disabilities, allocating shorter trips to wheelchair-bound riders and hiring a blind software engineer.

(Image: United Overseas Bank (UOB). People with autism account for about one-third of the 53 employees at UOB’s Scan Hub, where customer documents such as credit card application forms are scanned, classified and archived.)

(Image: United Overseas Bank (UOB). People with autism account for about one-third of the 53 employees at UOB’s Scan Hub, where customer documents such as credit card application forms are scanned, classified and archived.)

To raise more public awareness and support, the inaugural Shaping Hearts Festival 2021 invited about 150 community artists with special needs to present artworks and performances over a two-week event in November 2021.

Other ground-up initiatives include the Purple Symphony, an orchestra of over 100 musicians who are differently-abled. This was founded by Member of Parliament Denise Phua, a champion of people with disabilities in Singapore. Meanwhile, the Inclusive Arts Movement was started by pianist Ron Tan, who is hard of hearing. Such initiatives have opened many Singaporeans’ eyes to differently-abled talents and inspirational stories.

(Image: The Purple Symphony Facebook page)

(Image: The Purple Symphony Facebook page)

Volunteerism in Singapore

Many Singaporeans have come forward to help one another, and in recent years, there has been an upward trend in volunteerism in Singapore, especially among retirees.

Charities like Temasek Foundation and Lien Foundation have also stepped up. Temasek Foundation has funded initiatives that include offering mothers from vulnerable families a community health and social care support system from pregnancy until the child turns three years old, and empowering children from low-income families to chase their dreams in dance and art. Meanwhile Lien Foundation has been investing in the eldercare sector, creating more centres for seniors to exercise, undergo health checks or socialise, as well as more quality nursing homes equipped with facilities such as a gym and cafe.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Singapore’s volunteerism rate dropped to 22 per cent in 2021, down from 29 per cent in 2018. The study, conducted by the National Volunteer and Philanthropy Centre (NVPC), said that this was likely because many people were unable to be physically present for the activities due to COVID-19 restrictions.

However, that does not mean that Singaporeans’ spirit of volunteerism has waned. The same survey showed that 56 per cent of those polled were likely to volunteer over the next few years.

The pandemic also changed the way people helped each other out. More Singaporeans moved to offer skills-based volunteering online, such as doing pro bono training programmes for lower-income students or small businesses or social workers, noted NVPC.

They were also more involved in ground-up non-profit organisations working with various community groups affected by the pandemic.

Such groups included: (1) low-income families whose breadwinners were unable to work due to COVID-19 and kids could not do home-based learning due to lack of internet access; (2) home-bound elderly and those with disabilities who need vaccinations and medical care; and (3) migrant workers, stuck in their living quarters due to circuit breaker measures.

To encourage more volunteer groups to tackle community needs arising due to the pandemic, the SG Strong Fund was set up in 2020. The fund raised more than $550,000 for 150 projects . These causes include Project Wellness, which distributed cloth masks and care packs for hospitalised individuals and nursing home residents, and 6th Sense, which distributed devices and data cards for children who needed to do home-based learning.

Young “digital volunteers” were among the many Singaporeans who offered their time and hard work. For example, some volunteered to help small and medium enterprises (SMEs) upskill their staff or upgrade their digital platforms. Others responded to the SG Digital Office (SDO) ‘s call for digital ambassadors to help senior citizens pick up digital skills. They participated in the 60 SG Digital Community Hubs set up islandwide, teaching tens of thousands of seniors how to stay connected with their family and community, navigate digital government services, conduct e-payment via their smartphones, and more.

At the same time, older Singaporeans have stepped forward to contribute by helping other seniors to learn about healthy ageing, preparing food donations, cleaning up beaches, and serving as befrienders to Singaporeans of different backgrounds.

With Singapore’s ageing demographics leading to an increase in senior volunteers, organisations such as RSVP Singapore are creating programmes for senior volunteers. In 2019, RSVP Singapore signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth’s (MCCY) Singapore Cares Office (SG Cares Office) to grow senior volunteerism. RSVP Singapore hopes to tap the wealth of skills and expertise that our seniors have to benefit the community whilst remaining active in the community.

The silver lining of the pandemic is that it has opened up new means of volunteering through online and digital initiatives like zoom-based training sessions that can benefit a regional audience and peer-to-peer fundraising.

These online volunteering initiatives focus on imparting skills to non-profit organisations, SMEs, social workers and other groups who need professional help. This addresses one of social service agencies’ most important challenges, in upgrading and upskilling to improve their digitalisation, fundraising and management of manpower and volunteers, according to a 2020 survey by the National Council of Social Services.

The SG Cares Office is also working with national intermediaries to grow skills-based volunteerism among working professionals such as accountants and lawyers. Organisations such as the Pro Bono SG (formerly known as Law Society Pro Bono Services) and the Institute of Singapore Chartered Accountants partner local community organisations to curate volunteer opportunities for skills-based volunteers to meet community needs.

Acts of Care

With potential fault lines and divisions in our society, it is important that we take active steps to build bridges and care for one another. Singaporeans may often be seen as cold and tend to keep to ourselves, but many times when push comes to shove and when it matters, we step up.

In March 2003, a deadly then-unknown virus made its way from Hong Kong to Singapore via a Singaporean former flight attendant. Within a month, the virus – later named the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) – spread to over 100 people on the island, killing four. There was widespread fear in dealing with the deadly disease, and alarm and panic that soon turned into discrimination against healthcare workers.

Taxis and buses refused to stop at Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH), the designated screening and treatment centre for SARS. Neighbours did not want to ride the lift with nurses. Queues at food courts would quickly shorten when a nurse joined the line. After hearing about these incidents at a dialogue with TTSH staff, Dr S. Balaji, then-Minister of State for Health highlighted the issue to the media, who then made the public aware of these discriminatory, fearful practices.

There was an outpouring of tributes to healthcare workers on the SARS frontline, with some Singaporeans writing in to forums to condemn discriminatory behaviour towards them, while others sent food, drinks and bouquets to TTSH.

Image: Messages of Thanks for the Staff at Tan Tock Seng Hospital during the 2003 SARS Crisis

Image: Messages of Thanks for the Staff at Tan Tock Seng Hospital during the 2003 SARS Crisis

Singaporeans also expressed support for their work with initiatives such as the Peach Ribbon Campaign, in which members of the public wore peach satin ribbons to show appreciation for healthcare workers. Those who got the ribbons were encouraged to make a small donation to the Courage Fund, which was set up to provide relief to SARS victims and healthcare workers. In less than two months, the campaign raised S$322,121 for the fund.

There are other examples where Singaporeans gladly helped others. In 2015, when the transboundary haze from Indonesia hit Singapore and the Pollutant Standard Index (PSI) readings hit hazardous levels forcing schools to shut, local kindness movement “Stand Up For Singapore” started a fund-raising campaign called “I Will Be Your Shelter”. They aimed to buy air purifiers and filters for the elderly and needy in the North Bridge Road area. The campaign raised over S$6,000. Another Singaporean, Cai Yinzhou, started the “3000 masks, 1 Singapore” project, where he distributed masks to the elderly and migrant workers, while a hardware store at Block 442, Clementi Avenue 3 was spotted bearing a sign in English and Chinese that read: “free mask for children and senior citizens”.

Left: I Will Be Your Shelter. Right: 3000 masks, 1 Singapore.

Left: I Will Be Your Shelter. Right: 3000 masks, 1 Singapore.

Similarly in 2020, as the world fought to control and contain the COVID-19 pandemic, Singaporeans once again stepped up to help others. One Singaporean couple gave out 6,600 surgical masks for free when they saw how Singaporeans were scrambling to find masks. While another couple made their own alcohol-based hand sanitiser and shared it with their neighbours by placing a bottle at the lift.

Even our daily lives, Singaporeans have shown love and compassion to others. One couple opened their home to young people in need, quitting their jobs in the process. Mr Kenneth Thong and his wife, Adeline, started The Last Resort — a home for young adults operating out of a rented four-storey terraced house in Seletar. The young adults who stay with them could be unwed mothers, homeless teenagers or those with mental problems. Most are from dysfunctional families and have nowhere else to go, and many are too old for institutional care or fostering. “We want them to experience what a normal, safe, functional family looks like. And that means they are free to have whatever we have here,” said Mr Thong in an interview with The Straits Times in 2018.

While there are many of these heartwarming examples, fostering a caring and inclusive society still requires constant nurturing, and getting people to look beyond the boundaries of their class lines.

Conclusion

In Singapore, there are many opportunities to interact with one another regardless of background, whether in schools, workplaces, community organisations or neighbourhoods. However, building a caring and inclusive society takes a society of people with the heart and desire to take action and help one other at all times. This is what will amplify individual work to collective, community effort.

We continue to work towards equal rights to people of all races and religions, forging a national identity that brings Singaporeans together, and building a society that is inclusive and caring. The journey towards a Singapore that will stay united against all odds is one that is still in progress and up to generations of Singaporeans to achieve.