Building a Multicultural Singapore

Building a Multicultural Singapore

Singapore’s location on the crossroads of trade between the East and West, has drawn a diverse mix of people here for hundreds of years. Our multi-racial and multi-religious identity began long before we attained independence as a nation.

Interactions between the different ethnic groups, however, were limited under British rule. The British government had assigned separate areas for the different communities: the Chinese downtown, the Malays in Kampong Glam and Geylang Serai, and the Indians in Serangoon and Sembawang.

This segregation hindered the development of mutual understanding and trust between communities. “Each group clung to its own clan or dialect community for security. There was no social cohesion. We were a divided society,” former Minister for National Development S. Dhanabalan said at a New Year gathering for community leaders on 6 January 1989.

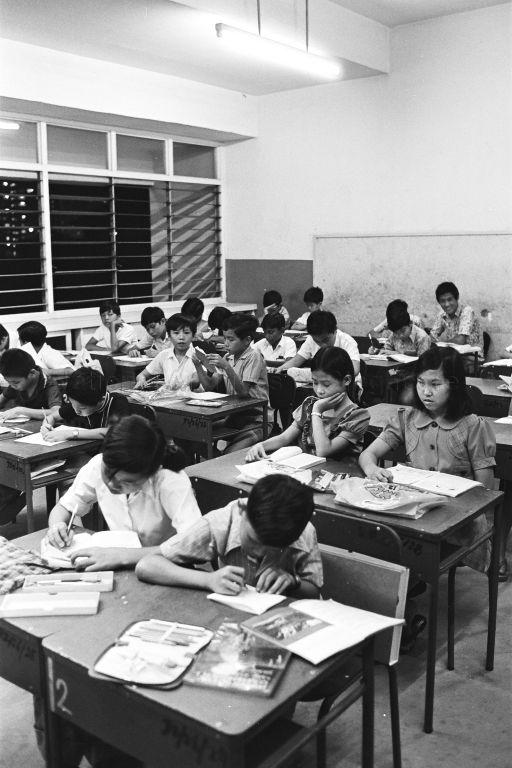

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

In 1964, Singapore encountered one of its worst riots. On 21 July, 23 people lost their lives and another 454 were injured following a scuffle between the Chinese and the Malays during a procession to celebrate the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday. The riots reignited in September, killing 13 people and injuring 106. Five years later, another racial riot broke out, leaving four dead and 80 injured.

The racially-charged riots of 1964 and 1969 showed how easily ethnic tensions could be exploited to thrust the nation into turmoil. Singapore’s early leaders recognised that race and religion were potential fault lines that had to be addressed, if Singapore were to progress.

(Image: Ministry of Education, Singapore)

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

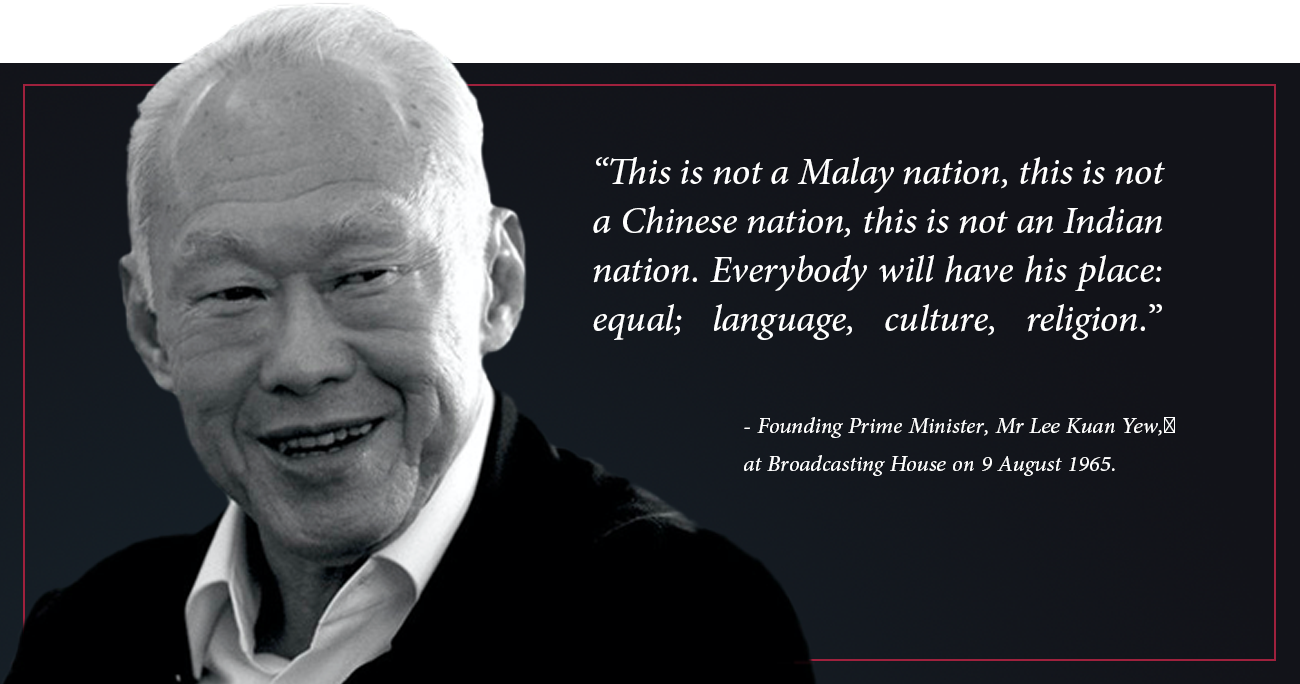

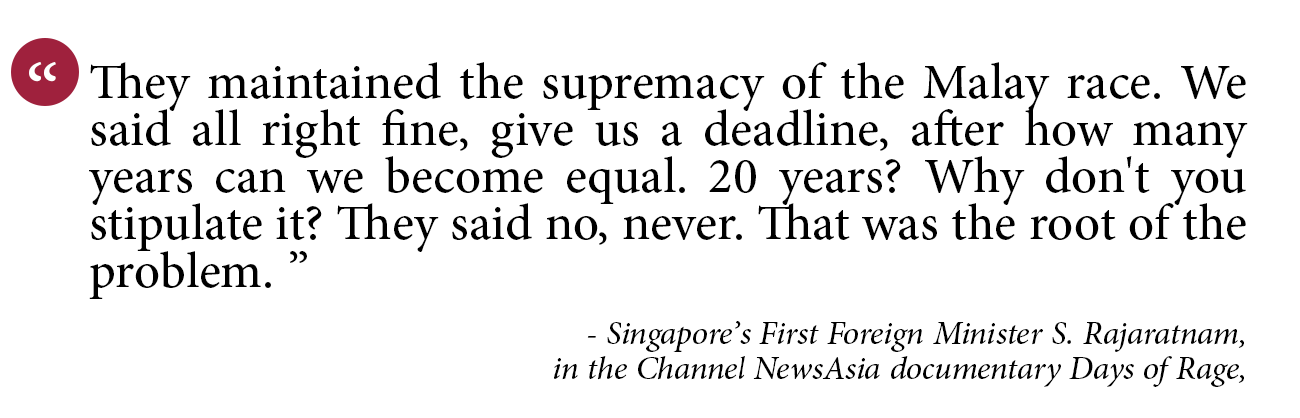

This issue was the key reason why they made the painful decision to separate from Malaysia in 1965. The Malaysian leaders wanted a “Malay Malaysia”, not a “Malaysian Malaysia”. They saw Singapore’s multiracial slogan as a challenge to Malay dominance. It was a disagreement that could not be resolved.

Having experienced racial politics, where the majority Malay race in Malaysia was favoured, Singapore’s founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew understood the need for meritocracy and equality. When Singapore separated from Malaysia, our leaders drummed into Singaporeans that each citizen is equal, regardless of race, language or religion.

.jpg)

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

In his first speech to the United Nations General Assembly on 21 September 1965, then-Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam described Singapore as a “little United Nations in the making” where four cultures – Malay, Chinese, Indian and Western – were allowed to develop freely and equally.

Maintaining Racial and Religious Harmony

The commitment to equality of races is not simply recited in our pledge; it is enshrined in our Constitution, which states that no citizen has more or less rights than another citizen. Singapore is also a secular state which does not favour any religion, nor allow religious preferences to dictate the affairs of the state, whether in the enactment of laws or in the areas of public policies.

A Presidential Council for Minority Rights was established to safeguard the rights of minorities and to ensure that the government does not pass laws that discriminate against any race or religion.

And while the freedom to practice religion is protected, the government introduced the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act (MHRA) in 1990 to encourage tolerance and moderation among different religious groups, and to guard against rising religiosity. The Act was updated in 2019 to reflect changes in the way information is spread among the population and to protect Singapore against foreign influence.

Besides safeguards against discrimination, measures were also taken to help people of different ethnicities for bonds. Our leaders chose a common language to unite the different ethnic groups. This was necessary in Singapore as there were multiple languages and dialects. In the past, the Chinese mainly spoke dialects such as Teochew, Hokkien and Cantonese, while the majority of Malays spoke Malay and the bulk of Indians spoke Tamil. Before independence, the education system also comprised private Chinese-, Malay- and Tamil-medium schools, which were more popular than government-run English schools.

Hence, the government introduced English as the language of administration and instruction. This unified Singaporeans without privileging any particular cultural group while also promoting international trade and diplomacy. Singaporeans continued to retain their mother tongues as second languages, to access their cultural heritage and strengthen their values and sense of cultural belonging. Moreover, it retained Malay as our national language, as Malays are constitutionally recognised as the indigenous people of Singapore.

(Image: Ministry of Education)

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

Another way the government sought to bridge gaps along racial lines was to increase opportunities for interaction and build familiarity with other practices and customs, so that Singaporeans see themselves as part of a larger community of diverse people.

The Housing Development Board’s (HDB) Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP) was introduced to do just that. Aimed at preventing the formation of ethnic enclaves and to promote the integration of minority groups, it specified the proportion of flats that could be owned by the various ethnic groups. This created a more balanced ethnic mix in the various housing estates.

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

In just three decades, HDB estates have become a microcosm of society, with a mix of residents of all races. The abundance of common spaces, including coffeeshops, fitness corners and community centres, has also made it easier for residents of different races to gather, mix, and play.

Residents have also largely accommodated one another's practices and customs. Cultural and religious practices such as the burning of joss paper and incense during Hungry Ghost Festival, prayer sessions at void decks during Ramadhan and the annual foot procession by Hindus during Thaipusam have largely gained acceptance among all ethnic groups. There have also been instances of the various ethnic groups celebrating the festivals of other races. For example, they would visit the homes of friends and neighbours of different ethnic groups during national holidays like Chinese New Year, Hari Raya Puasa, and Deepavali.

Building and Maintaining Religious Harmony

As a multi-religious society, Singapore protects the freedom to practise religion while maintaining harmony among the various faiths.

Inter-religious harmony is essential for a densely populated city-state like Singapore, ranked the world’s most religiously diverse country in a 2014 Pew survey.

Amid the growing polarisation in race and religion across many parts of the world, the harmonious co-existence that we enjoy should not be taken for granted. In a 2019 Gallup World Poll, Singapore was ranked top out of 124 countries for tolerance of ethnic minorities, and 95 percent of respondents stated that for racial and ethnic minorities, Singapore was “a good place to live”. This was higher than the global average of about 70 per cent .

In the same year, a Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY) survey found that eight in 10 Singaporeans were satisfied with relations between different races .

This positive view was supported by the growing levels of friendship and trust between Singaporeans of different religions: a study by the Institute of Policy Studies and racial harmony advocacy group OnePeople.sg released in 2019 found that 59 per cent of respondents said they could trust either “more than half” or “all or mostly all” people of a different faith to help in a national crisis, compared to over 51 percent in 2013 .

More Singaporeans said they have close friends of another race in 2018 compared to five years ago. In 2018, Malays and Indians were more likely as in 2013 to have at least one Chinese friend than not. For instance, 77.2 per cent of Indian respondents said they had a close Chinese friend, up from 63 per cent in 2013, according to the same 2019 IPS survey . Similarly, while 23 per cent of Chinese respondents had a close Malay friend in 2013, this proportion rose to 30 per cent in 2018, indicating increasing levels of racial harmony and inter-racial interaction.

This racial and religious harmony is not a natural state for Singapore, nor was it easily cultivated.

Efforts to forge mutual understanding and awareness about different beliefs and practices were already underway long before Singapore gained independence.

A key milestone in Singapore’s history of multi-religious engagement was the formation of the Inter-Religious Organisation (IRO) after the end of World War II. Founded in 1949, the IRO serves to promote friendship and cooperation among members of different religions. It originally represented six religions: Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, and Sikhism. Over the years, it has expanded to include Zoroastrianism, Taoism, the Bahá'í Faith and Jainism.

The IRO played a pivotal role to help calm the population during the 1964 racial riots. Members of the IRO visited those injured during the riots. At the same time, its leaders rallied Singaporeans around the common goal of working for “the national good” by issuing regular speeches calling for understanding on broadcast on radio, newspapers and television.

When Singapore gained independence, former PM Lee Kuan Yew pledged to build “a multiracial nation where every community…can integrate fully, yet have maximum space to maintain their identities and practise their faiths, customs and way of life.” His vision was reflected in the constitution of Singapore, which guarantees the right of religious freedom for all people, as long as the religious activities do not violate laws on public order, health, or morality.

Over the years, Singapore has continued to promote religious harmony and unity through interfaith community initiatives, combined with secular policies, careful planning and governance. Today, the IRO is involved in many local activities and events, and plays an important role in educating the Singapore public about different religions.

Dubbed a “secular state with a soul” today by Singaporean diplomat Zainul Abidin Rasheed, Singapore has reflected Mr Lee’s vision by building physical places of worship and a strong social acceptance of our multi-religious culture and heritage.

Places of worship as part of social and cultural capital

Singapore’s urban planning policies design Places of Worship (PWs) as social amenities, incorporating religious institutions into the broader community. In HDB towns, new PWs are generally located near or within neighbourhoods for the convenience of worshippers.

The location and design of the PWs are planned to optimise land usage while reflecting the character and history of the surroundings.

One example of a PW carefully preserved and integrated into the housing estate is the “tree shrine” in the middle of Toa Payoh town centre. This ficus tree dates to the colonial days and served as a prominent landmark in the kampung area, where it stood steadfast even during Toa Payoh’s redevelopment in the 1960s. A Buddhist shrine, “Ci En Ge”, was later built next to the tree and is an essential site for worship and community events today.

Image: The Ci En Ge shrine is devoted the the spirit that lives in the Banyan Tree behind it.

Today, some PWs also serve as centres for advancing interfaith understanding and religious harmony. One example is the Harmony Centre housed in the An-Nahdhah Mosque in Bishan. Opened in 2006 to promote a greater understanding of Islam and Muslims, it showcases exhibits and artefacts on inter-religious relations in Islamic history, civilisation and lifestyle, and other religions in Singapore.

Another urban policy design that promotes religious cohesion is the inclusion of common spaces like void decks, amphitheatres and community centres in our neighbourhoods. These spaces hold social and religious functions such as weddings, funerals, and prayers, creating opportunities for residents of all backgrounds to enhance their understanding of one another’s practices and beliefs.

Many PWs with unique architecture have also become important heritage sites. As the Urban Redevelopment Authority puts it, they are “brick-and-mortar repositories of memories and…treasured focal points for diverse communities”.

For instance, the 1.7 km heritage trail in the Bras Basah-Bugis precinct has several PWs in close proximity to each other, including Bencoolen Mosque, Maghain Aboth Synagogue, and the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd. These sites have deep historical and cultural significance dating back to pre-independent Singapore. Stories about their harmonious co-existence and how religious groups have found common ground can be found in the Harmony in Diversity Gallery currently situated in Maxwell Road.

Singapore’s multi-religious heritage is also seen in the rich diversity of religious practices. The National Heritage Board has paid tribute to such practices by compiling an intangible cultural heritage list . These practices include the Baha'i faith practised by about 2,000 believers in Singapore and the Passover, which some 2,500 Jews commemorate.

Building strong inter-religious communities

Singapore’s multi-religious diversity has benefitted our society in various ways, such as a proliferation of interfaith collaborations for charitable and social causes. One such partnership was a joint interfaith tuition programme by Heart of God Church and Khalid Mosque for secondary school students in their congregations and the neighbourhood . The church and mosque took turns holding the tuition sessions, and this offered both the tutors and students opportunities to learn more about each other’s faith.

Strong bonds across faiths are key to religious harmony. While our faiths may be different, we share common values, such as charity, love, respect, and empathy. It is important that we continue building and maintaining meaningful relationships with others of a different faith, while expressing our own religious beliefs respectfully and sensitively.

Meanwhile, many interfaith organisations have been set up over the years to promote religious harmony from the ground up. The National Steering Committee (NSC) on Racial and Religious Harmony, which comprises top-level leaders from the major faith and ethnic groups, has created safe spaces for dialogue on issues such as religious harmony and common space in Singapore.

Racial & Religious Harmony Circles serve as local networks fostering trust among different community segments such as grassroots and religious leaders and worshippers. Members are also trained in crisis response, so they are prepared to preserve solidarity and maintain calmness among their communities in a crisis such as a terrorist attack.

Another example would be hash.peace, a youth-led advocacy group which serves to develop programmes for sustainable social harmony. For example, hash.peace supports the efforts of Religious Rehabilitation Group (RRG) in Singapore by speaking out against groups and individuals with radicalised views.

(Image: hash.peace)

Legislation to safeguard religious harmony

The Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act (MRHA), enacted in 1990, aims to prevent friction and misunderstanding among different religious groups. It also provides the Government with the necessary powers to maintain religious harmony while safeguarding the separation of religion and politics. For example, it allows restraining orders to be issued against those who cause feelings of hatred and enmity between different religious groups.

In 2019, the Act was amended to safeguard against foreign actors exploiting religious fault lines in our society amid the growing threat of foreign religious interference.

"In the nearly 30 years since MRHA was enacted, we look around us. Al Qaeda, ISIS, communal violence in Myanmar, Sri Lanka and more. There are disputes between all major religions across the world, and abuse of religion by politicians and religious leaders,” Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam told Parliament when the changes to Act were passed on 7 October 2019 .

Mr Shanmugam added that Singapore had previous incidents of religious disharmony, which were handled with “wisdom and common sense”.

Under the amended Act, more safeguards were put in place to protect local religious organisations against foreign influences . For instance, religious groups will be required to disclose single foreign donations that are above S$10,000 for the Government to assess if there is negative foreign influence.

In addition, the president, secretary and treasurer of a religious group must be a Singapore citizen or permanent resident. The majority of the executive committee or governing body of a religious group must be Singapore citizens.

Aware that social media can enable offensive posts to go viral within seconds, the Government updated the MRHA’s restraining order (RO) to take swift action against such posts. Under the amended Act, an RO can be issued against a religious group to pre-empt, prevent or reduce any foreign interference affecting the group that may undermine religious tolerance between different religious groups in Singapore and present a threat to public peace and public order in Singapore.

Mr Shanmugam noted that the MRHA is one of the tools used to promote religious and racial harmony as a critical tenet of Singapore’s society. "We draw lines in the sand. We reinforce positive norms, and they make our society stronger. It is not just the MRHA that has helped keep religious harmony in Singapore. It is a whole series of policies, approaches, and most crucially that a significant majority of our people accept, subscribe to, and support these policies and want religious harmony. It is a core value of our society,” he said.

Online space for peaceful religious discourse

Public discourse about how online space is being used today to promote or undermine religious harmony in Singapore has intensified, especially with the increase in online religious content during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Internet is a medium that allows for the exchange of views among Singaporeans of different religions, thus encouraging greater engagement and solidarity. At the same time, caution must also be exercised to ensure social tensions are not inflamed in online discourse.

Singaporeans’ attitudes differ about how tolerant we should be of religious extremists posting their views online. A 2019 IPS survey found that 26.8 percent of 4,000 respondents surveyed were open to religious extremists posting their opinions online or on social media. This percentage was much higher for respondents aged 18 to 25, with almost 50 percent stating that such views can be aired .

This suggests that younger Singaporeans tend to be more open to online discourse about race and religion. But they are also more exposed to the risks of destabilising online voices that threaten religious harmony.

To educate the public on terrorism, extremism and the risk of self-radicalisation, the Ministry of Home Affairs has conducted online courses and engaged over 90,000 residents on emergency preparedness skills through the national movement SGSecure. The non-profit Religious Rehabilitation Group has also raised awareness against religious radicalisation .

Recognising that younger generations respond well to a community-driven approach to religious discourse, the youth-led interfaith initiative Roses of Peace has trained youths to become peace ambassadors and interfaith leaders over the past few years. The non-profit organisation has been equipping youth with digital media advocacy and public speaking skills to build bridges among various religious communities and organise interfaith activities involving over 3000 young volunteers.

Meanwhile, a church and a mosque in Geylang Serai went on TikTok to engage youths and create opportunities for them to learn about each other’s faiths.

(Image: Screengrabs from Tiktok)

New areas of racial and religious diversity

Maintaining racial and religious harmony continues to be a work-in-progress, as Singapore’s social fabric changes and belief systems become even more diverse with the influx of new immigrants.

Some Chinese temples here are seeing more Chinese immigrant worshippers with different practices. The migration of Northern Indians to Singapore has led to differing approaches in the local Hindu population, mostly from Southern India.

For all these new groups, the task remains to help them integrate into our multi-religious society. But just as any religious believer or group must adhere to Singapore’s laws and not propound disharmony and violence, these groups also need to contribute to upholding Singapore’s social harmony.

Religious harmony a continuous work in progress

In 2021, a spate of incidents stoked public discourse.

In June 2021, an Indian man posted a video of a Chinese woman hitting a gong in an apparent attempt to disrupt him as he conducted Hindu prayers and rang a religious bell at the doorway of his HDB flat. The video went viral, prompting a police investigation and igniting a lively online discussion. While many Singaporeans expressed sympathy for the Indian man, others debated the disturbance caused by religious practices such as religious chanting or incense burning in a shared space.

Another incident that has attracted national attention is the “Tudung issue”.

The Way Forward

The tudung issue, as well as recent racist acts such as a Chinese man kicking an Indian woman while uttering racist slurs and a Malay lady hurling racist insults at an Indian commuter, have prompted much national discussion about the way forward for religious and racial harmony.

In a forum on race and racism held in June 2021, Minister of Finance Lawrence Wong called on Singaporeans of different backgrounds to reflect on how to better understand one another, as “tolerance without real understanding cannot work”.

These “worrying incidents have given us pause to consider the state of our racial harmony”, he said. “We clearly cannot leave things as they are. We are better than this. Whether online or offline, we must hold ourselves to higher standards, and tackle racism wherever it exists in our society.”

Having more open discussions about different beliefs and identities is in itself a step in the right direction.

For older Singaporeans, many tended to treat this as a taboo subject in the past, looking to the force of the law to effectively manage religious fault lines. An IPS study in 2019 found that seven in 10 Singaporeans aged 65 and above felt that the Government is responsible for racial and religious harmony in Singapore, compared to just half of respondents aged 18 to 25 who felt this way.

Hence, it is timely and essential to engage older Singaporeans in more discussions about their personal views about different races and religions. They can become more involved in a “whole-of-society” effort to foster inter-religious understanding through taking part community-led initiatives such as Regardless of Race Dialogues by OnePeople.sg and A Tapestry of Sacred Music by The Esplanade Co Ltd which are funded by the Harmony Fund.

As for the younger generations, they have expressed a stronger preference for a more community-driven approach to race and religion rather than looking to state intervention. They also respond well to dialogue and community efforts to help those who may face issues arising from racial or religious differences. This is reflected in the IPS survey, which found that young Singaporeans are more sensitive to discrimination and are more likely to investigate a message that claimed a business refused to serve a person from a certain race or religion.

The amendment to the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act in 2019 reflects this paradigm shift by incorporating softer touches that focus on persuasion and rehabilitation, while encouraging moderation and tolerance between different racial groups . One example of these softer touches in the Act is vesting the authorities with powers to order someone who has caused offence to stop and make amends, by learning more about the other race. The Act also seeks to encourage offending parties to take part in activities that can mend ties with the aggrieved persons in the religious community.

Under this Act, the Community Remedial Initiative (CRI) was introduced to allow people who have hurt the feelings of another religious community to make amends to the affected community and learn more about our multi-religious society. Examples of remedial actions may include a public or private apology to the aggrieved parties, or participation in inter-religious events.

Such touches can promote peace-building and soothe religious tensions, while still making clear that Singapore laws absolutely do not accept views that denigrate people of different backgrounds or beliefs.

Building Common Ground Amid Diversity

While national policies and legislation have done much to promote social harmony, it is also being maintained at the individual and grassroots level.

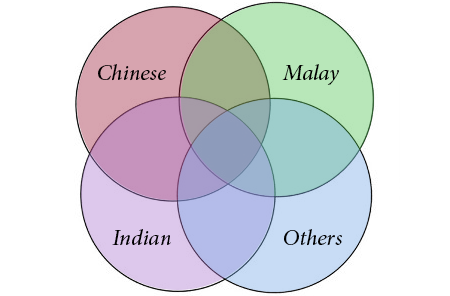

Singapore uses the “overlapping circles” model to deal with issues related to race – a concept first introduced in the 1960s by then-Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam, In 1999, then-PM Goh Chok Tong referred to it as he spoke about the creation of a Singapore “tribe”. At the PM’s Forum at the Nanyang Technological University on 11 May 1999, then-PM Goh explained that each ethnic community is envisioned as a circle, and Singapore aims to maximise the overlapping areas between the circles. We preserve the culture and customs of each ethnic group while creating shared beliefs and norms.

In contrast, the melting-pot approach, would have meant that minority communities would be absorbed by the majority.

Our unofficial visualisation of the overlapping circles model

The efforts to promote racial and religious harmony, by building common ideals and norms in the “overlapping circles” as well as having room for diversity, have contributed to developing a foundation of mutual trust and understanding between ethnic and racial communities.

This was most clearly seen during the arrest of 15 Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) members in Singapore in December 2001. Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks by Al-Qaeda in the United States in September 2001, JI terrorists had planned to bomb diplomatic missions and attack nationals of Australia, Israel, the United Kingdom, and the United States in Singapore.

Then-PM Goh was concerned that revealing that a Singaporean Muslim's involvement in JI could affect the confidence and attitude of non-Muslim Singaporeans towards their Muslim neighbours. However, as he mentioned at the opening of East-West Dialogue on 16 November 2005, the trust in the community allowed these attempted acts of terrorism to be discussed openly. This trust lies both between the government and the Muslim community, and between Muslims and other communities.

In the aftermath of the JI arrests, Inter-Racial Confidence Circles (IRCC) were formed in 2002, to act as a critical bridge between racial and religious leaders, and promote inter-faith interaction and understanding. In the event of any racial and religious conflict, the IRCCs act as first responders to quell any brewing tension among the various ethnic groups and reestablish peace.

The key value of the IRCC network is “to make sure that in times of peace, we build relationships, trust and confidence. This will create a safety net for Singapore.” said then-Minister for Community Development, Youth and Sports Vivian Balakrishnan in 2008.

On January 2016, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) released news of the arrest of 27 radicalised Bangladeshis in Singapore, who were contemplating carrying out acts of armed violence overseas. In May that year, another 8 Bangladeshi men were detained for planning to stage terror attacks back in Bangladesh, and for intending to join terror group ISIS as foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq.

Many ministers came forward to speak on the incidents, including then-Labour Chief Chan Chun Sing who urged Singaporeans “not allow this incident to affect the strong ties we share with our fellow Muslim Singaporeans as religious harmony is the cornerstone to our unique heritage in Singapore”.

Understanding that this was the act of radicalised individuals and not reflective of the whole Muslim community, Singaporeans were aligned with the government's approach in treating terrorism as a national security problem that affected Singaporeans -- regardless of race or religion.

With the community's trust and support, the government was therefore able to act quickly and ensure other Singaporeans did not turn against Muslims in the community. This could have disrupted social cohesion and strained community relations.

The Continued Need for Racial Harmony

Social resilience is Singapore's key strategy against terrorism and domestic conflict, and ensures that we do not fracture irreparably along the fault lines of race and religion. Reducing racial and religious tension through cooperation and understanding between communities is critical in preventing future acts of violence in Singapore.

But a lapse could tear open old wounds. Singapore the remains ever vigilant in monitoring tensions from racial differences, and we take proactive steps to safeguard our ability to stay united.

In recent years, some events have led to conversations in society on whether racism is built into our system. In particular, the 2020 George Floyd protests in the United States revived discussion around issues of race and privilege, with the term “Chinese Privilege” coming into common usage. Many locals have also come forward to share their experiences of casual and systemic racism in the recent ‘Regardless of Race’ dialogues in 2019, with some questioning the continued relevance of Special Assistance Plan (SAP) and Singapore’s Chinese-Malay-Indian-Others (CMIO) racial framework.

These conversations have the potential to promote greater empathy and compassion amongst Singaporeans, allowing minority voices to be heard and questions asked. By listening to one another and clarifying our doubts, we learn how to better show compassion and consideration for one another, and how to create a more equal and harmonious society.

Such conversations are important in a variety of contexts. In particular, older Singaporeans, or those who grew up in single-race communities, may have more misconceptions and biases towards other races, which need to be dispelled through frank and open conversations with those they trust.

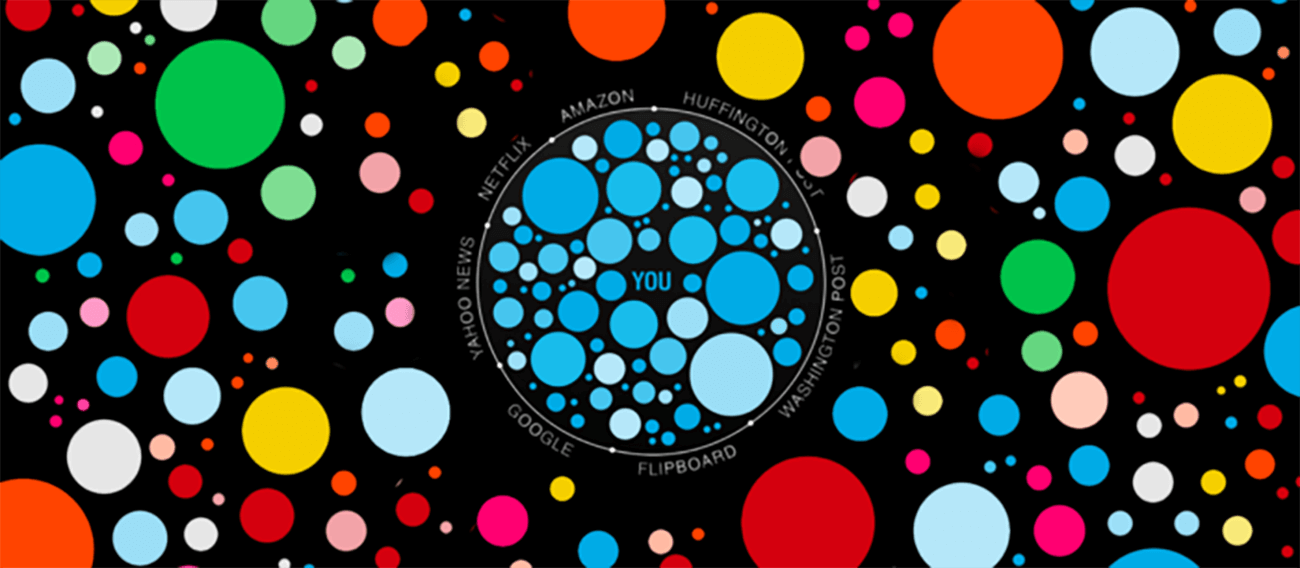

Moreover, there is a tendency for social media platform algorithms to create “filter bubbles” for users where information we dislike or disagree with is automatically filtered out. This increases the risks of “echo chambers”, where we have an inaccurate perception of reality, because we see only or mostly news that we like or agree with. Our social media feeds could mislead us into thinking only our view is right.

Image Courtesy of Eli Pariser TED Talk: Beware Online Filter Bubbles

To prevent our social media feeds and those of our friends from becoming echo chambers, we need to consciously look out for people with opinions different from our own to converse with them, and share articles or commentaries from a range of perspectives. We need to also be aware of accounts that spread fake news or cause hate, by those who seek to destabilise our society. Calling out the inaccuracies in these posts and having conversations with those who share them, helps protect the unity we enjoy as a society.

(Image: Ministry of Education, Singapore)

“We are not completely colour-blind, and this makes a difference. It will influence our thinking and choices, either consciously or unconsciously,” said PM Lee Hsien Loong, in a speech on multiculturalism at a PA Kopi Talk on 23 September 2017, shortly after Madam Halimah Yacob was sworn in as Singapore’s first Malay president in 47 years. Singapore, he said, “continues to require guide-ropes and guard-rails to prevent us from falling off along the way.”

Last updated on: 26 April 2024